A century ago the first labour exchanges opened to great acclaim. But despite the many advances, are their successors meeting their clients’ needs, asks Graham Snowdon

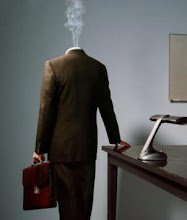

Jobcentres are a mixed blessing: you only attend one if you are out of work, and for many people they embody the frustration of applying for benefits or of trying to find new employment when jobs are rarer than hens’ teeth.

But on 1 February 1910, when the UK’s first 62 labour exchanges – the forerunners of today’s Jobcentre Plus network – opened their doors, interest and demand was huge. “Promising start everywhere” proclaimed the following day’s Manchester Guardian with reports of hundreds of people queueing outside offices.

With situations vacant ranging from piano regulators to picture frame gilders, labour exchanges brought new order to the hitherto chaotic process of finding work. “Before then, people would have found work through word of mouth and by visiting factories,” says Dr Ian Gazeley, senior lecturer in economic history at the University of Sussex. “There were some rudimentary public works schemes but for most, the only way to get a job was to go directly to the employer.”

Offices had separate rooms for men, women, employers and children and, as Winston Churchill – then president of the board of trade in the Asquith Liberal government – noted, each was painted green: “the colour of hope”, he said after visiting the Hackney labour exchange on its opening day.

Jobcentre Plus today has 750 offices and about 78,000 employees offering an integrated service incorporating benefits and employment search. Stepping inside is like walking into the foyer of an ultra-modern bank. Where once there were partitions and noticeboards with job vacancies on cards, now there are touch-screen “job points” and personal advisers to hand.

“We’ve seen huge changes in the service and how it helps people in the past 100 years, even in the past 10 and five years,” Yvette Cooper, work and pensions secretary, said at a new exhibition about labour exchanges in Hackney this week. “Getting away from the culture of the Full Monty and the benefit screens has been important.”

Loss of motivation

On the face of it, the service has never been so joined up. Yet as they turn 100, can jobcentres really still claim to be meeting the needs of the people they now call their “customers”? Figures released this week by the Liberal Democrats, showing more than 210,000 people seeking work in the construction industry but just 302 such vacancies available on Jobcentre Plus’s website, seem to embody the problem.

Outside the jobcentre in Hackney, opinion is mixed. Darren, aged 29, is an unemployed security guard who has been using the service on and off for about 12 years. “I’ve never found one job through the jobcentre,” he says. “I’ve been sent on a lot of courses, but when you come in here, use the job points and make a phone call, nine out of 10 times they’ve all gone. You lose motivation to keep coming back. I’ve got more jobs from going to agencies.”

Cassandra, a recent psychology graduate, has been looking for jobs for a year and is now focusing on temping work rather than anything related to her degree. “It’s not working out very well,” she says. “When I send out my CV no one ever gets back in touch.”

She wants Jobcentre Plus to help make introductions for her with potential employers: “When you send emails you don’t get any feedback, so you don’t know what you’re doing wrong.”

Not everyone is down on the jobcentre, though. Louise, a 27-year-old chef, has only been visiting it for a few months but her impressions are largely positive. “I think they’re pretty good,” she says. “I haven’t signed on before, so I’ve got nothing to compare it with.” She admits she had to ask about training and that there seemed like plenty of work on the job machines, “but it’s just not necessarily what I’m after”.

Yet still the perception remains that Jobcentre Plus is not geared to the needs of many people who have lost their jobs in this recession. Several readers commenting on a recent Guardian website article about a day in the life of a jobcentre were scathing.

“Demoralising and frustrating,” commented sansucre, referring (coincidentally) to the Hackney jobcentre. “The staff are badly informed, and just don’t care.” “The main problem seems to be that the whole system is geared towards finding low/unskilled work,” posted TheGraduate.

It’s a view shared by 54-year-old Steve Wood from Southampton, who spent 38 years working in the semiconductor industry before it collapsed last year. “The job went, the company went, and so did the business from Europe,” he recalls. Jobcentre Plus, he says, has been “a dead loss”, although he is quick to support the staff: “They do a great job for what they were set up for, which is blue-collar workers. For white-collar workers, basically they didn’t have a clue.”

Hoping to reinvent himself as a web designer, Wood sent off 220 job applications in six months and received only one interview offer. Eventually he tried Jobcentre Plus after hearing about government initiatives to help unemployed people like himself. “But they didn’t know anything about it. There was no real help at all.”

Exasperated and in need of a project, Woods set up the website Whitecollarunemployed.co.uk, aiming to share information with people in a similar predicament. It has given him practical experience and led him to some interesting contacts, but his jobseeker’s allowance, which is only paid for the first six months, has now stopped and the future is uncertain. “I’m still not earning enough to pay my bills,” he says.

Recruitment issues

It’s not just those looking for work that feel let down by jobcentres, either. Research conducted last year by the Federation of Small Businesses (FSB) showed fewer than one in five of its members were using Jobcentre Plus to recruit. The FSB’s national chairman, John Wright, claims his members are ignored by a service that appears to offer them precious little for the £3.36bn Jobcentre Plus spends each year. “We are concerned the lion’s share of funding goes to large companies and multinationals,” he says.

But Graham Houghton, Jobcentre Plus’s district manager for the City and East London area, insists such criticism is unfounded. “It’s simply not true,” he says. “The bulk of our vacancies are for smaller local businesses. We have account managers who go out and visit small businesses to help them with their recruitment needs. Maybe there’s an issue in getting small businesses to come to us more, but those that work with us are overwhelmingly satisfied.”

While admitting there are problems with Jobcentre Plus, Richard Exell, a senior policy officer at the TUC, also feels they get a lot of unwarranted negative publicity. “The service suffered a series of cuts a few years ago,” he points out. “But the fact is there has been a recession and there aren’t many jobs around, and that’s not Jobcentre Plus’s fault. There are far fewer horror stories now than in the past.” So are we asking too much from jobcentres now? Is it unfair to expect staff to be consistently empathetic and knowledgeable? Are we expecting them to magic jobs out of nowhere?

Seen in the context of Britain’s 19th-century poor laws, by which the impoverished unemployed would end up in the workhouses, Churchill’s labour exchanges represented a radical shift in thinking. William Beveridge, best known as an architect of the post-war welfare state, was a driving force behind the plans. “The labour department at the Board of Trade at the time was quite forward-looking,” says Gazeley. With the passing of the 1911 National Insurance Act, benefit payments followed soon after.

Labour exchanges were eventually renamed employment exchanges but their function remained largely unaltered until 1973, when the first jobcentres opened. Steve Gill, now Jobcentre Plus’s external relations manager for Surrey and Sussex, worked through the transition. “The old employment exchanges were like backstreet offices, a bit grim,” he recalls. “We used to interview people in cubicles and there were enormous queues, often out of the door.” All the jobs were simply kept in a drawer. “You would just offer them to people who asked if there were any jobs.”

Benefits were paid in cash, using a system leaving something to be desired by today’s standards. “We’d put the money in a bag and wrap it up in string, then seal it with sealing wax,” Gill says. “Each member of staff used to have a crown with a number. You stamped your crown on the ceiling wax, so when you came in the next morning, you could tell if the seal had been broken.”

How times have changed. Last week, Cooper set out a broad future vision for Jobcentre Plus in which more information and services will be made available to people online, and predicted it would soon reach out to those already in work, “to help people progress and rise up the career ladder”.

For those in need of inspiration, it could be worth bearing in mind that jobcentres are countercyclical employers. “Because of the unemployment situation, we are recruiting,” points out Houghton. “We’re now hiring a lot of good people who are enabling us to do a lot of good things.

“Probably about 60 or 70 people who have joined me over the past few months are ex-financial services people, who have experience of having been made redundant and who have experience of Jobcentre Plus services.”

Perhaps something small but good has come of the credit crunch after all.

A brief history of jobcentres

1908 Winston Churchill appointed president of the board of trade; draws up plans for labour exchanges

1909 Parliament passes act to launch the labour exchange

1910 In February the first 62 labour exchanges are opened

1916 The ministry of labour is formed

1945 Founding of welfare state

1973 Jobcentre network opens

1975 Sex Discrimination Act bans sex discrimination

1986 New Job Training Scheme and Restart interviews introduced

1987 Jobcentres become part of Department of Employment, operating alongside benefits offices

1996 Unemployment benefit and income support merge to become jobseeker’s allowance

1997 New Deal programmes give people on benefits extra help to find work, with training and career advice

2001 Department for Work and Pensions formed

2002 Jobcentre becomes Jobcentre Plus

No comments:

Post a Comment